What is “the future”? Science fiction has taught us to associate the words “cutting-edge” and “state-of-the-art” with this concept. We may imagine fantastic cityscapes and sleek, hi-tech gadgets and vehicles and advanced robotics and artificial intelligence. Many of us think of space travel, spaceships and alien planets and lifeforms. However, not all visions of the future are one and the same. What we citizens of the 21st century might imagine to be the future is completely different from what people from the biblical times, the medieval times, the Renaissance, and 19th and 20th centuries envisioned.

The early 20th century was the period when people seriously started asking the question, “What will the future look like”? Specifically, the concept of Utopia— an ideal society with a benevolent system of governance and perfect living and social conditions— first came to prominence during this period. Two important events in history helped shape this way of thinking, namely, the Russian Revolution and the First World War.1 The aftermath of these two bloody revolutions brought forth a collective sense of dissociation from previously established norms and traditions, as well as a yearning for a more peaceful society in general.

This was further compounded by questions of what role the arts and humanities had in creating this new future, particularly how these disciplines would work in conjunction with science and technology. Artists were faced with the challenge of becoming a force of cultural, ideological and social change, and needed to learn how to work with new technology in order to do so. The role of artists in achieving a Utopian future is perhaps best exemplified in a quote by the visual artist Constant Nieuwenhuys— who created his concept for an anti-capitalist future city, New Babylon, in the 1960s and declared that “Artists are no longer trying to escape the reality of social life, but they are trying to change this reality.”2

A Utopian future during the late 1910s to early 1920s was “a dream of a world in which things would be different”, according to Theodor Adorno in his essay On Lyric Poetry and Society.3 During the period after World War I in particular, a Utopian future was conceived to be one where humans and machines lived in harmony and prosperity. Technological innovations such as the X-ray, radio, telephone, automobile and airplane helped accelerate daily life and consequently gave birth to an optimistic world view. For the people living during this time, technology was the key for mankind to reach perfection.4

This is actually not so different from the sci-fi fueled ideas of the future that we 21st century citizens have. Countless books, TV shows, movies and video games have featured a distant future where humans and machines co-exist. The main difference lies in the fact that we are more open to deconstructing this concept, questioning whether or not machines really are the solution to humanity’s problems. The people of the early 20th century, however, were steadfast in their belief that machines, science and technology can only benefit mankind and contribute to the achievement of Utopia.

Going back to the role of the artist in realizing the future, the proliferation of the belief of harmony between man and machine thus gave rise to movements in art and design known as Utopian Modernism. These include Suprematism, Constructivism, Bauhaus and De Stijl. While these movements were vastly different in their values and objectives, they were all primarily concerned with similar concepts: abstraction, man’s relationship to the spiritual, man’s relationship to the machine, and of course, visions of the future.

In my previous post, I discussed the idea of whether or not a popular fictional character can still be recognized even when placed in a different time, place and cultural understanding. This week, I’d like to tackle a similar question: What would an ultramodern sci-fi setting look like based on the aesthetics, values and ideals of a Utopian Modernist movement from the early 1900s?

To answer this question, I’d like to discuss a design movement which I feel has been the most influential in the development of our current understanding of the very concept of modernity itself— the Bauhaus.

A Brief Overview of the Bauhaus Movement

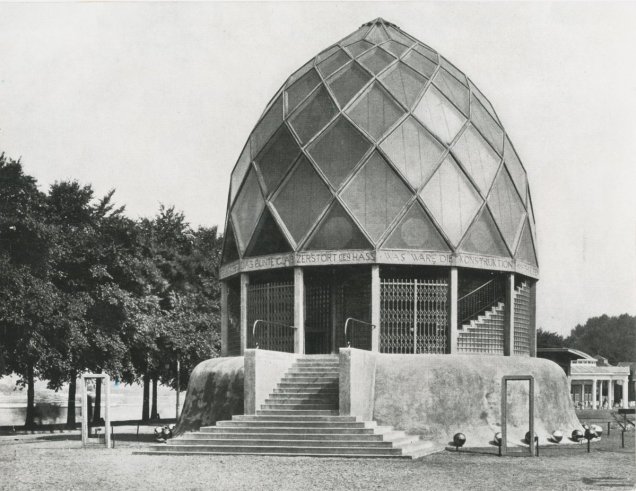

The Bauhaus was founded by architect Walter Gropius in the city of Weimar, Germany in 1919. It was a school that sought to train artisans and designers that would shape a new utopian future through the arts and architecture. 5 The ultimate goal of the movement was the unification of these two disciplines, in which there was no distinction between monumental and decorative art.6 Inspired by the technological advances in the aftermath of the First World War, one of the movement’s main objectives was also to forge a healthy relationship between man and machine.

Students entered into a curriculum that aimed to bring back the apprenticeship system from the time of the Early Renaissance, where aspiring painters, sculptors and craftsmen trained under the master of a particular workshop. After a certain amount of time under the mentorship of the workshop master, these individuals would then “graduate” and become journeymen who would travel, accept commissions, and eventually join a guild and become a master themselves.7 Training at the Bauhaus was divided into three courses of instruction, appropriately named “Apprentice”, “Journeyman” and “Junior Master”.8

The preliminary course focused on the fundamentals of drawing and painting and was taught by visual artists such as Paul Klee, Vassily Kandinsky, and Oskar Schlemmer. The secondary course was taught by Johannes Itten (later Josef Albers and László Moholy-Nagy) with the course in general encouraging students to “unlearn” the clichés of European art academia.9 The Bauhaus curriculum was structured in a way that was interdisciplinary— students who were accepted at the school were immersed in the fields of not only the fine arts, but also crafts, architecture, design education and theory, and science and technology.10

The school’s ambitions eventually proved too financially impractical however, and the program had to be restructured. In 1923, the school shifted its goals into utilitarian design for mass production, adopting the slogan “Art into Industry” in the process. 11 The school moved from Weimar to Dessau in 1925, where Gropius designed the new campus building. This would later become one of the hallmarks of modernist architecture.

Gropius stepped down as director in 1928 and was succeeded by Hannes Mayer, who restructured the curriculum to put even more focus on designing for mass production and the public good. Meyer, a Marxist, was forced to resign by the right-wing municipal government and was subsequently replaced by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in 1930. Mies van der Rohe moved the school to Berlin and updated the curriculum once more, this time increasing emphasis on architecture. The school itself unfortunately only lasted until 1933 and was shut down by the Nazis. Many of the movement’s founders immigrated to the United States during World War II.12

Despite the school’s closure, Gropius, Breuer, Albers, Moholy-Nagy and Mies van der Rohe continued to teach at various universities in the States, thus ensuring that the Bauhaus’ values and philosophies would endure, and as a result influenced a new generation of architects and designers.

Design Problem: Conceptualize a 1920s Bauhaus Martian Colony

With this basic understanding of what the Bauhaus was and how the movement made an impact on modern design and architecture, I’d like to go back to the question I had at the beginning of this post. What would an ultramodern sci-fi setting look like based on the aesthetics and philosophies of the Bauhaus? Specifically, what would a 1920s Martian Colony look like if it were built by the designers and architects of this movement?

This project will not go into the minutia of the actual feasibility of space travel and colonization during the 1920s. This is sci-fi, after all, and some suspension of disbelief is needed. Rather, the objective is to be able to translate the fundamental ideologies and aesthetic sense of the movement into a genre that would otherwise be completely foreign to people from this time period.

Breaking Down the Bauhaus Aesthetic – Architecture, Industrial Design and Graphic Design

The Bauhaus curriculum covers a wide variety of disciplines and crafts, but for the purposes of this project, I will be doing a formal breakdown of the courses most pertinent to the subject matter of futuristic urban living. These are: architecture, industrial design, and graphic design.

Architecture and Urban Structure

Firstly, we’ll try to understand the logic behind the designs of Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, two of the most prominent architects from this movement.

Walter Gropius expressed a belief in the reunification of aesthetic sensibility with utilitarian design due to his experiences with the Deutscher Werkbund (German Association of Craftsmen), of which he became a member in 1910. He established his own architecture practice with Adolf Meyer that same year, and carried out his first main work, the Fagus Werk Shoe Factory in Alfeld-an-der-Leine. Gropius utilized reinforced concrete for the framework of the building, allowing it to be sturdy enough for the corners to be made of glass. He later applied the same style to his Werkbund Exhibition in Cologne in 1914, where he and Meyer displayed several office and factory buildings. Throughout his career, Gropius used industrial architecture as an icon for the socio-cultural opportunities of modern society.13

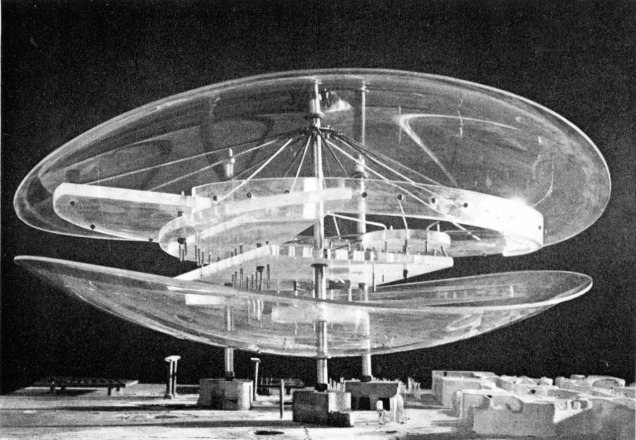

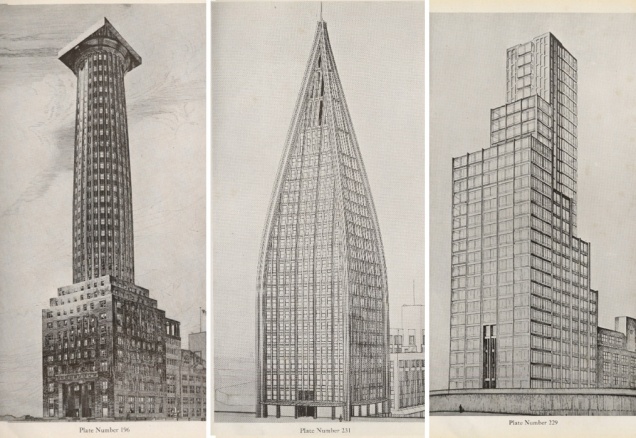

In 1922, Gropius and Meyer participated in the Chicago Tribune Building Competition, the goal of which was to design “the most beautiful office building in the world”.14 Gropius ultimately lost the competition and John Howells and Raymond Hood’s Gothic-inspired design (the building that stands to this day) took the prize. In spite of the loss, Gropius’ groundbreaking ultramodern entry, along with those of Adolf Loos, Bruno Taut and Max Taut, helped pave the way for 20th century skyscraper design.

At the same time, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe was conceptualizing his own “skeletal” skyscrapers— buildings with a visible steel framework that utilized glass windows in lieu of load-bearing exterior walls. He designed the 20-story Friedrichstrasse Office Building (also known as the “Honeycomb”) in this style. His idea of using a skeleton to hold a building together without having the need for outer walls was untested at the time and considered to be highly unorthodox. The building would have had a central utility core that held the main elevator system, similar to present-day skyscrapers. The building would have been built on a tight, maple leaf-shaped triangular property— this sectioning would have achieved optimum lighting and ventilation, in addition to having manageable, aesthetically sophisticated interior rooms.15 Mies used glass in such a way that his designs seemed to suggest not just an office building, but also a spiritual crystal cathedral, hinting at Utopian sentiments.16 His fondness for glass is evidenced by several of his designs from the 1920s, particularly that of his famous all-glass skyscraper, which he designed in 1920-21 and exhibited in 1923.

While many of his buildings were never built in Mies van der Rohe’ lifetime due to the technological limitations of construction, the influence of his designs was such that many 21st century buildings like the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, The Shard in London, and the Gate to the Orient in Suzhou, China would follow in his footsteps.

To summarize, the main characteristics of Bauhaus architecture are as follows:

Lines are very important in Bauhaus architectural design in general. True to the Bauhaus credo of reducing objects to their most basic geometric forms, buildings are appropriately composed of straight lines and 90-degree angles. Likewise, the shapes implemented in these architectural designs are also grounded in fundamental geometric forms, particularly the square, rectangle and triangle.

Materials played an important factor in both Gropius’ and Mies van der Rohe’ designs, with the latter himself stating that, “No design is possible until the materials with which you design are completely understood.” Both Gropius and Mies favored glass, though the latter was more liberal in his use of the material than the former. Gropius always tended to have some sort of framework to support the glass, such as reinforced concrete and steel, whereas Mies had his trademark “skeletal” approach that would show off as much glass as possible and do away with exterior walls. In both cases, the two architects recognized the potential of glass as a building material, which would prove influential in the development of architecture later on in the century.

Lastly, space is a crucial element of Bauhaus architecture. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe said, “We must be as familiar with the functions of our building as with our materials. We must learn what a building can be, what it should be, and also what it must not be.” The spatial aspect of designing a building had to be taken into careful consideration and every room and structure needed to have a purpose. Gropius’ and Mies van der Rohe’s style of architecture share a common trait in this respect, as they are both based on the viewer “looking into” the inside of the building from the outside.

Industrial Design

Bauhaus industrial design is best exemplified by sleek, heavily stylized forms have become associated with modernity. Much like architecture, breaking down objects into bare geometric forms was stressed, as was functionality and ease of use. Perhaps the most well-known Bauhaus designers in this discipline were Marcel Breuer and Marianne Brandt, who specialized in furniture design and metalwork, respectively.

Marcel Breuer was one of the early adopters of contemporary furniture design. Initially starting with traditional wooden tables, dressers and cabinets, over time he moved on to metal furniture. Breuer’s preferred material was extruded steel tubing, inspired by the frame of a bicycle.17 He believed that conventional forms could be “dematerialized”, or brought down to their minimal existence. This line of thinking eventually drove him to pioneer ultra-sleek, lightweight and mass-producible chairs— the design theory of which would later be spread to furniture as a whole.

Breuer also hypothesized that traditional chairs supported by four legs would become obsolete in the future, believing that they would be replaced by columns of air.18 From 1925 he had developed a comprehensive collection of tubular steel furniture, the most famous being the B3 Chair, later renamed the Wassily Chair. While this was indeed a step forward for Breuer to achieving his envisioned “chair supported by air”, it was his rival Mart Stam who succeeded with the creation of his Cantilever Chair, which later led to a patent lawsuit.19 Interestingly, this enmity involuntarily led to the birth of an entirely new genre of chair design which persists to this day, most commonly seen in the form of computer chairs.

Marianne Brandt, the first woman to attend the metalworking workshop (eventually appointed studio director in 1928), likewise created designs of household objects that would become iconic of the Bauhaus aesthetic. Brandt is best known for her line of geometric silver and ebony wares consisting of tea pots and infusers, kettles, and pitchers. The appeal of Brandt’s wares comes from her knowledge and manipulation of the material, implementing the use of hemispheres and cylinders, circular and triangular shapes, and tilting devices.20 Her Tea Infuser with its non-drip spout and heat-resistant handle is perhaps her best known work.

All metal and glass elements used by the metal workshop were produced with the help of machinery, once again stressing the mass-reproducibility of their designs and objects. Brandt used the same industrial technology in her work, using it to chrome-plate her brass bowls, ashtrays and platters, which she designed specifically for reproduction.21

In addition to her famous kitchenware, Brandt also designed the Kandem Bedside Lamp with Hin Bredendieck. This is a design that not only shows her versatility, but also transcends time and would not look out of place in a present-day home or interior decorating store.

In summary, Bauhaus industrial design can be best described by the following characteristics:

Both straight and curved lines are used in conjunction, oftentimes to completely reimagine the silhouette of a pre-existing, familiar object. Marcel Breuer’s Wassily Chair is a good example of this, as it can easily be recognized as a chair but at the same time, was something alien and unorthodox at the time of its introduction. Marianne Brandt applied a similar approach, however she emphasized shape more than line. Her repertoire of metalwork takes common household items and breaks them down into simple forms such as spheres and half-spheres, cylinders, triangles and circles.

Materials again play an important role in Bauhaus industrial design. The members of both the furniture and metal workshop were encouraged to experiment not just with conventional materials such as wood and leather, but also with newer developments such as extruded tubular steel and chrome. The introduction of these new resources allowed designers like Breuer and Brandt to explore new design choices and directions, while at the same time staying true to the essence of whatever object they sought to replicate.

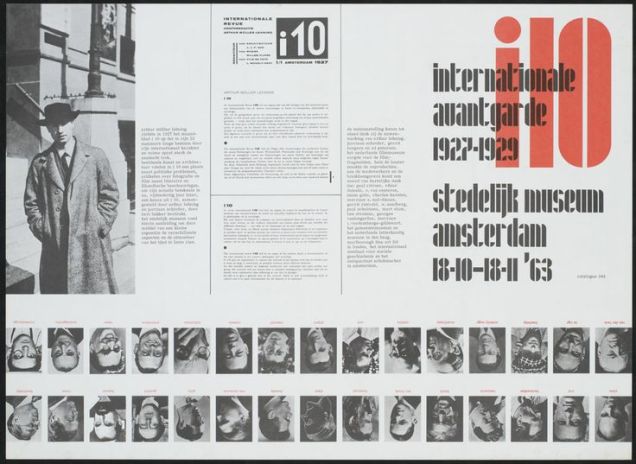

Graphic Design, Advertising and Typography

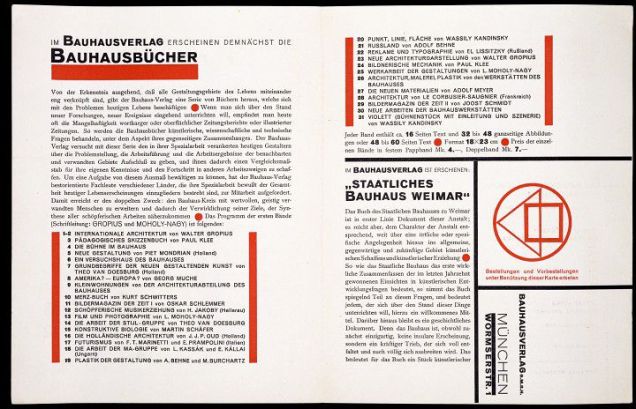

Typography and graphic design were initially not among the main priorities of the Bauhaus, but grew in importance as the school depended on presenting itself in a positive light to the public. Johannes Itten, László Moholy-Nagy, Joost Schmidt, Josef Albers and Herbert Bayer helped to promote advertising graphics very strongly during the school’s tenure in Weimar. Self-promotion eventually gave way to a genuine pursuit of furthering the use of visuals and text as an effective means of communication, and the typography, printing and advertising workshop was soon at the forefront of innovation. They proliferated the use of capital letters and sans serif fonts for increased legibility. At the same time, text was combined with colors and geometric forms to create visual harmony that was pleasing to the eye.22

The Hungarian designer László Moholy-Nagy can arguably be called the father of modern graphic design. He introduced a new element to the field of typography and graphic design by combining it with his accumulated knowledge of visual communication techniques. From 1923 to 1928, Moholy-Nagy served as editor of the Bauhausbucher, a series of 14 books that acted as the manifesto of the Bauhaus faculty, as well as the Bauhaus Zeitschrift fur Bau und Gestaltung (Bauhaus Magazine for Building and Design). His style was influenced by his experiences with Constructivism— he frequently made use of the colors black and red, along with solid horizontal and vertical lines in his layouts. Communication was his main priority, however spatial organization and aesthetics remained important. In order to achieve this, Moholy-Nagy introduced the use of “new” and “elementary” typography in the form of the Grotesque and Futura typefaces. These highly legible fonts opened up the opportunity for typography oriented towards purpose.23 This new type of design, which made use of the Gestalt Principles of Grouping24 was not only aesthetically pleasing, but also scientifically functional.

Moholy-Nagy further developed the discipline of graphic design by incorporating photography into his workflow. Initially, he created photomontages (or “photoplastics” as he called them) inspired by the Dada Movement that mostly served as social commentary. Over time, he also began to use photomontage for commercial work such as advertisements, book jackets, and magazine covers, justifying his design choices as being true to the Bauhaus philosophy that “there is no barrier between commercial and fine art”.25

Interestingly enough, for the longest time photography had been frowned upon in the field of advertising and graphic design, but during Moholy-Nagy’s tenure at the school, its value was recognized as an object-oriented (and therefore objective) artistic means and method of visual communication.26 Photography was actually not formally taught at the Bauhaus until 1929, though it had become extremely popular as an extracurricular activity among the students from 1923 onwards.27 When Herbert Bayer took over the typography and advertising workshop in 1928, the model created by Moholy-Nagy remained effective and the use of photographs in graphic design became more prominent in the 20th century, eventually becoming a standard that persists to this day.

Once again, the main characteristics of Bauhaus graphic design are as follows:

The use of lines is very important in both the visuals and the text. Moholy-Nagy in particular developed sans serif typefaces that allowed for the most legibility, and used solid bars and lines of varying thicknesses to accentuate the text in his layouts. The shapes he used were simple circles and squares and mostly served as an extension of the lines and text.

Colors are limited to black and red— a remnant of Moholy-Nagy’s previous Constructivist experiences. Red proved to be a very effective color for emphasis, and was used for accentuating the header titles of articles as well as important parts of the body text. Moholy-Nagy’s use of the color red in advertising and graphic design was a turning point that influenced the industry for the rest of the 20th century. By the 21st century, it has become a standard. Nowadays, using red for emphasis is a common practice that can be found in magazines, movie posters, web design and video game user interface elements.

Value comes into play with the incorporation of photography. Moving away from his previous, intentionally jarring Dada-esque satirical photomontages, Moholy-Nagy used photography alongside text in his layouts, coining the term “typophoto”28 and using them to enhance his compositions. Photographs and the introduction of value added a new layer of three-dimensionality that was previously unheard of in graphic design.

Lastly, the clever use of space is another of Moholy-Nagy’s most significant contributions to the field of graphic design. The combination of new sans serif typefaces, lines, shapes, colors and photos warranted a new means of spatial organization. Moholy-Nagy achieved this with the use of Gestalt Principles, grids and careful measurements that resulted in layouts that are clean, understandable and aesthetically pleasing.

Designing a Bauhaus Martian Metropolis

Part I – Conceptualization

“Designing is not a profession but an attitude. Design has many connotations. It is the organization of materials and processes in the most productive way, in a harmonious balance of all elements necessary for a certain function. It is the integration of technological, social, and economical requirements, biological necessities, and the psychological effects of materials, shape, color, volume and space. Thinking in relationships.”

Before I began creating thumbnail sketches for this project, I turned to the above quote by László Moholy-Nagy for inspiration. In doing my research for this project, I realized that it was not Gropius, nor Mies van der Rohe, nor Breuer, nor Brandt who would be the best philosophical reference. While they continued to be my primary references in terms of aesthetics, for the actual thinking behind the designs, I believe Moholy-Nagy’s voice was the most suitable choice. This is because Moholy-Nagy, who was a firm believer of social idealism, had a more holistic, objective worldview of technology and designing for the public good.

For this project, my thesis statement is once again a quote by Moholy-Nagy:

“Equal right for everyone to coequal satisfaction of his needs— such is the goal of all progressive work today. Technology and its capacity for mass production of commodities has to a great extent levelled and raised the niveau of humanity.”29

My idea for this assignment was to have a progressive society that considers technology and innovation to be the main aspect that guides their daily lives. Machination, industrialization and mass-production plays an important role in the citizens’ lives. However, rather than deconstructing this notion and having the stark, commercialized society often seen in present-day dystopian media, I chose a more optimistic, straightforward approach. Technology is the key to the betterment of humanity. I’ve chosen several quotes by Moholy-Nagy to support this ideology, which I have also quoted verbatim for the written copy in my brochure.

“A dwelling should be not a retreat from space, but life in space.”

“The reality of our century is technology: the invention, construction and maintenance of machines. To be a user of machines is to be of the spirit of this century.”

“The experience of space is not a privilege of the gifted few, but a biological function.”

My premise is that the Earth has become corrupted in the aftermath of the Great War, and in an effort to save mankind from moral and cultural stagnation, the solution would be to start anew in our neighboring planet, Mars. Because art and the artist are active agents for the improvement of society, they’ve taken it upon themselves to build a new home— a giant Metropolis for all the former inhabitants of Earth to share.

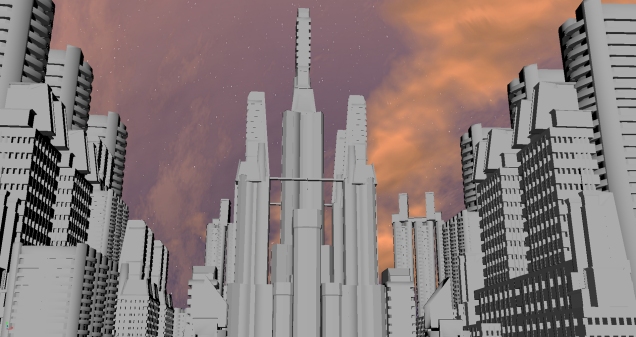

To protect the citizens from the harsh, arid landscape, the city is composed of megastructures and skyscrapers that each have suitable living conditions on the inside. Much of the logic behind the city is based on the theories of Hugh Ferriss in his book, The Metropolis of Tomorrow. I chose to reference only Ferriss’ theories and not his own drawings of envisioned cities of the future, in part because his architectural style is more in line with Art Deco than it is with Bauhaus. Ferriss, however, provides valuable input on the various characteristics of a futuristic megacity, two of which I found pertinent to this project:

“THE MOST POPULAR IMAGE of the Future City—to judge by what is most often expected from the draughtsman’s pencil—is composed of buildings which, without any modification of their existing nature, have simply grown higher and higher. The popular mind apparently is intrigued by height, as such. A 60-story tower in New York evokes a 70-story tower in Chicago. What is more serious, a 60-story tower in New York evokes a 70-story tower directly across the street. The skyscraper is said to be America’s premier architectural contribution to date, popular fancy pictures the future contribution to be rows of still higher skyscrapers; in other words, it pictures 70-story skyscrapers side by side for miles.”30

“THE CHURCH IN THE HEART OF THE CITY has of late become an interesting problem. It is a far cry back to the spired village edifice well set in its own spacious grounds, and a yet farther to the cathedral which dominated the Old World town. Trinity Church—still surrounded by its tombstones although looking directly down the axis of Wall Street—is today the unique exception. With skyscrapers towering above the spire of the average church, and with land values also mounting beyond its income, what is that church to do? Move away from the very arena whose activities it is, avowedly, to influence? We already have several examples of another solution—the church swallowed by the skyscraper; that is to say, the Church occupies the ground floor while an office building, or an apartment house, rises around and above it.”31

In addition to Hugh Ferriss, I also drew supplementary inspiration for city design and layout from both versions of the film Metropolis— the 1927 original by Fritz Lang, and the 2001 animated film by Katsuhiro Otomo (based on the comic by Osamu Tezuka).

I based the layout of the city on the progression system of the Bauhaus— the center is a large tower composed of several glass and steel skyscraper where the administrative powers or “Masters” reside. This will theoretically take the place of “the church in the heart of the city” since, for the Bauhaus, design and technology are a spiritual experience in and of itself. The buildings that surround this central structure radiate outwards by rank in descending order: “Junior Master”, “Journeyman”, and “Apprentice”. These buildings are dual-purpose— the upper floors serve as residential apartments, whereas the lower floors are offices and workshops. And in-line with the design thinking of Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, the materials I’ve implemented in my buildings are steel, concrete and of course, glass.

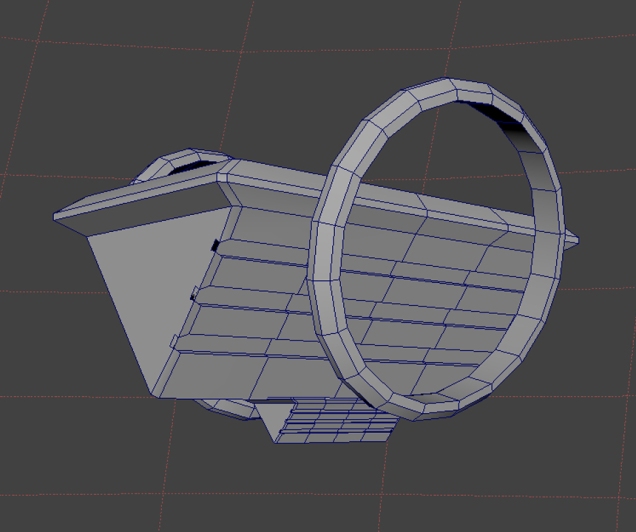

The main mode of transportation is the airship (based on the Zeppelin). This ship, which is about the size of a luxury liner, transports people from Earth to Mars. On Mars itself, smaller versions of the airship fly around the city and serve as public transportation.

The people who inhabit this city are based on the students, teachers, and affiliates of the Bauhaus— they are creative individuals who seek to improve society and the quality of life through the use of science, technology, art and design. Indoors, these citizens are garbed in fashion typical of the time period: broad-shouldered, V-tapering double-breasted suits for men; blazers, blouses and a choice of either skirts or trousers for the women. When outdoors, they wear specialized suits that allow their bodies to adapt to Mars’ atmosphere and gravity. I envisioned many of these spacesuits to have been created by the citizens themselves, and similar to the metal workshop at the Bauhaus, they can choose to replicate and mass-produce these with the help of machinery. Non-corroding metals, glass bowls, steel tubing and fiberglass-infused jumpsuits make up the spacewear. In order to overcome Mars gravity, special weights are worn on the arms and legs. Women also have “weight distribution stabilizers” on their hips.

In order to show aspects of life on this Martian colony, the use of a promotional brochure will be implemented. The brochure will contain both text and visuals that not only show the aesthetics of the Bauhaus movement, but also carry out its values and ideologies.

Part II – Production and Deliverables

I started with the “photograph” of the Martian Metropolis as it is the main focus of the brochure and the project in general. Initially I had tried using existing photos of architecture from the time period, but ultimately I found this method unsuitable since I could not find the right types of buildings and proper perspective. In order to work around this issue, I eventually decided to model my own buildings in Autodesk Maya and create my city from scratch. This proved to be a much faster and more efficient way of working, since I had the ability to manipulate the angle and perspective as I please. Also, I could easily duplicate and modify the buildings in the software, rather than having to do so manually in Adobe Photoshop. Overall, the process of creating my Bauhaus city took less than an hour.

Once I had finished modeling, I simply took a screen capture of the scene, which I then brought into Photoshop to paint over. I chose to use a 3:4 aspect ratio for my city “photo” in order to mimic the dimensions of photographs from the time period. This meant that my model had to be stretched lengthways in order to fit the canvas, but this didn’t prove to be an issue and actually helped to emphasize the verticality of the shot. Afterwards, I desaturated the image and adjusted the brightness and contrast levels to match the look of old photos. I also painted over the buildings to mask the digital look as much as possible. For the sky in the background, I added Mars’ two moons, Phobos and Deimos, in order to differentiate it from the Earth’s sky.

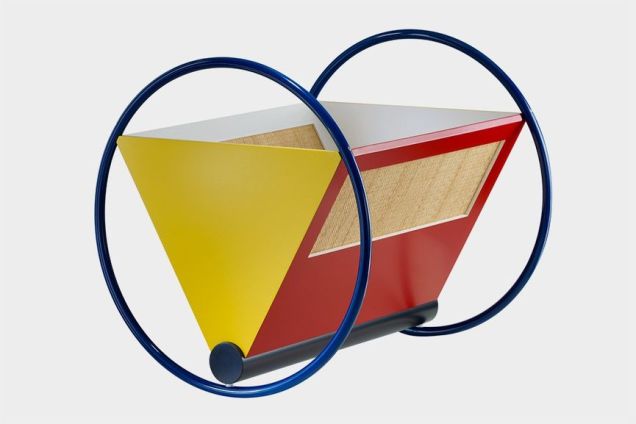

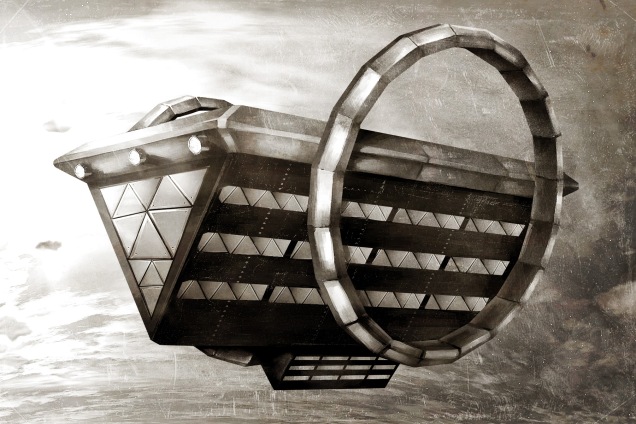

My Bauhaus Airship was also modeled in Maya, and I based the main design on the Bauhaus Cradle magazine rack designed by Peter Keler and also took inspiration from the Hindenburg and the Bathyscaphe Trieste. I modified some parts to make it appear more like an aircraft and less like a triangular magazine rack. For example, I moved the two rings from the ends of the prism to the sides in order for them to have the function of propellers. I also included windows on the sides and front, as well as arc lamps on the bow of the ship.

Besides the city and the airship, I also needed to show the citizens of Mars, in this case one man and one woman. In order to capture the aesthetic of the 1920s and 1930s and achieve a fair amount of authenticity, I directly sampled from black and white photographs from the period and then painted over them in Photoshop to achieve a unified look. The woman in particular is directly taken from one of Moholy-Nagy’s photoplastic compositions, Eifersucht (Jealousy). As for the man, his likeness is taken from stock photography of a man in a suit, however I modified his appearance to make him resemble László Moholy-Nagy himself.

For the man and woman’s spacewear, I combined aspects of Marcel Breuer and Marianne Brandt’s industrial designs with Oskar Schlemmer’s Bauhaus Ballet costumes32 as well as diving suits from the 1920s.33 Essentially, I wanted the male costume design to be composed mostly of blocky, angular forms and straight lines, whereas the female costume design is composed of circular and cylindrical forms.

For the man, many design elements were inspired by the Staybrite Silver Steel diving suit from 1925. The overall shape of his helmet is likewise designed after the diving helmets from the same time period. I also implemented the use of the extruded tubular steel that Breuer was fond of, using them for the breathing apparatus attached to the man’s helmet.

The woman’s spacesuit is heavily based on one of Oskar Schlemmer’s costume designs for the Triadic Ballet, although with some changes. First, I scaled down the size of the bowl-shaped helmet to roughly the same size as the man’s helmet. And rather than having clear plastic for the discs on the woman’s “dress”, I changed these into chrome plates similar to the ones created by Marianne Brandt in 1928, then added additional outer rings for fortification. The “dress” thus effectively becomes a “weight distribution stabilizer”.

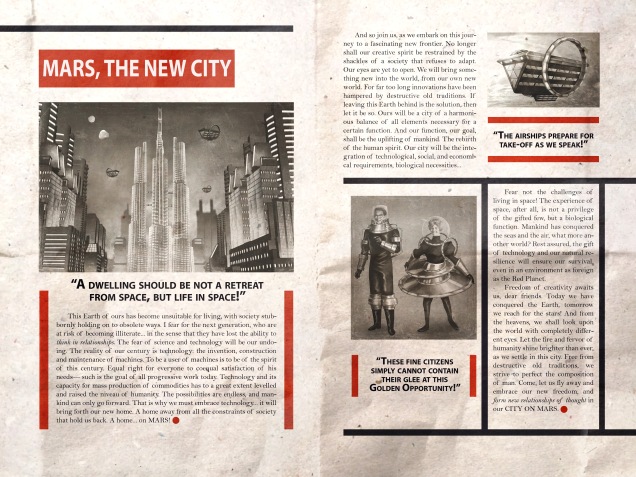

For the brochure inviting people to settle on the new city on Mars, I referenced Moholy-Nagy’s Bauhausbucher and Malerei, Fotografie, Film graphic design work, implementing the use of horizontal and vertical lines in black and red. While I initially wanted to create a three-page folding brochure, I found no period-appropriate prototypes. Two-page flyers and booklets were more common. I made sure to use capital letters and sans serif fonts for my heading and subheadings, meanwhile using print-legible serif fonts for the body text. The layout of the body text is “Justified” with hyphenation. At the end of important paragraphs, I’ve included sentence breaks in the form of red circles, which not only stay accurate to how Moholy-Nagy laid out his text, but also alludes to the planet Mars itself.

As mentioned previously, the actual writing in the brochure is heavily based on several quotes by Moholy-Nagy himself, albeit with some slight exaggeration to stress the significance of this breakthrough achievement. Some quotes have been included verbatim, while the rest of the copy text is original work that was written to match Moholoy-Nagy’s voice as much as possible:

This Earth of ours has become unsuitable for living, with society stubbornly holding on to obsolete ways. I fear for the next generation, who are at risk of becoming illiterate… in the sense that they have lost the ability to think in relationships. The fear of science and technology will be our undoing. The reality of our century is technology: the invention, construction and maintenance of machines. To be a user of machines is to be of the spirit of this century. Equal right for everyone to coequal satisfaction of his needs— such is the goal of all progressive work today. Technology and its capacity for mass production of commodities has to a great extent levelled and raised the niveau of humanity. The possibilities are endless, and mankind can only go forward. That is why we must embrace technology… it will bring forth our new home. A home away from all the constraints of society that hold us back. A home… on MARS!

And so join us, as we embark on this journey to a fascinating new frontier. No longer shall our creative spirit be restrained by the shackles of a society that refuses to adapt. Our eyes are yet to open. We will bring something new into the world, from our own new world. For far too long innovations have been hampered by destructive old traditions. If leaving this Earth behind is the solution, then let it be so. Ours will be a city of a harmonious balance of all elements necessary for a certain function. And our function, our goal, shall be the uplifting of mankind. The rebirth of the human spirit. Our city will be the integration of technological, social, and economical requirements, biological necessities…

Fear not the challenges of living in space! The experience of space, after all, is not a privilege of the gifted few, but a biological function. Mankind has conquered the seas and the air, what more another world? Rest assured, the gift of technology and our natural resilience will ensure our survival, even in an environment as foreign as the Red Planet.

Freedom of creativity awaits us, dear friends. Today we have conquered the Earth, tomorrow we reach for the stars! And from the heavens, we shall look upon the world with completely different eyes. Let the fire and fervor of humanity shine brighter than ever, as we settle in this city. Free from destructive old traditions, we strive to perfect the composition of man. Come, let us fly away and embrace our new freedom, and form new relationships of thought in our CITY ON MARS.

Once I had all my deliverables done, I added some finishing touches in the form of textures, scratches, and signs of water damage to give them a more authentic look.

And lastly, here are the final images:

And here is the brochure in its entirety:

WORKS CITED:

- David Ayers, Benedikt Hjartarson, Tomi Huttunen, and Harri Veivo, eds. Utopia: The Avant-Garde, Modernism and (Im)possible Life ( Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2015), 3-9.

- David Pinder, Visions of the City: Utopianism and Politics in Twentieth-Century Urbanism (Edinburgh: Routledge, 2005), 218.

- Theodor W. Adorno, “On Lyric Poetry and Society”, in Notes to Literature Volume One, ed. Rolf Tiedemann, trans. Shierry Weber Nicholsen, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991), 40.

- “History of Modernism”, Miami Dade College, accessed November 30, 2017, https://www.mdc.edu/wolfson/academic/artsletters/art_philosophy/humanities/history_of_modernism.htm.

- “Bauhaus Design Movement”, Bauhaus Movement.com, accessed November 15, 2017, http://www.bauhaus-movement.com/en/.

- “Manifesto of the Staatliches Bauhaus, Walter Gropius, April 1919”, Bauhaus Manifesto.com, accessed November 20, 2017, http://bauhausmanifesto.com/.

- Fred S. Kleiner and Christin J. Mamiya. Gardner’s Art Through the Ages: Twelfth Edition (Belmont: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning, 2005), 556.

- Maria Elena Buszek, “Bauhaus Manifesto and Program”, MariaBuszek.com, accessed November 27, 2017, http://mariabuszek.com/mariabuszek/kcai/ConstrBau/Readings/GropBau19.pdf.

- William J.R. Curtis, Modern Architecture Since 1900 (New York: Phaidon Press, 1982), 185.

- Buszek, “Bauhaus Manifesto and Program”.

- Alexandra Griffith Winton, “The Bauhaus, 1919-1933”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, accessed November 15, 2017, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/bauh/hd_bauh.htm.

- Ibid.

- Michael Siebenbrodt, and Lutz Schöbe. Bauhaus (New York: Parkstone International, 2012), 275.

- “The Chicago Tribune Competition”, The Skyscraper Museum, accessed November 30, 2017, http://skyscraper.org/EXHIBITIONS/PAPER_SPIRES/chitrib01.php.

- Siebenbrodt and Schöbe, Bauhaus, 278.

- Curtis, Modern Architecture Since 1900, 188-189.

- Winton, “The Bauhaus, 1919-1933”.

- Ibid.

- Siebenbrodt and Schöbe, Bauhaus, 224.

- Ibid, 243.

- Ibid, 251.

- Ibid, 157-158.

- Ibid.

- “Gestalt Principles”, Interactive Design Foundation, accessed December 8, 2017, https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/gestalt-principles.

- Hattula Moholy-Nagy, “László Moholy-Nagy – Biography”, Moholy-Nagy Foundation, accessed November 15, 2017, http://www.moholy-nagy.org/biography/.

- Siebenbrodt and Schöbe, Bauhaus, 160.

- Department of Photographs, “Photography at the Bauhaus”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, accessed November 15, 2017, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/phbh/hd_phbh.htm.

- László Moholy-Nagy, Malerei, Fotografie, Film (Painting, Photography, Film), 1927, 38-40.

- Ibid, 29.

- Hugh Ferriss, The Metropolis of Tomorrow (New York: Ives Washburn Publishing, 1929), 62.

- Ibid, 68.

- “Oskar Schlemmer’s Bauhaus costume parties (1924-1926)”, The Charnel-House, accessed November 27, 2017, https://thecharnelhouse.org/2013/06/02/oskar-schlemmers-bauhaus-costume-parties-1924-1926/.

- Vince Miklos, “The Strange and Wonderful History of Diving Suits, From 1715 to Today”, Gizmodo, accessed November 16, 2017, https://io9.gizmodo.com/the-strange-and-wonderful-history-of-diving-suits-from-1262529336.